wk 2 blue = present, black = absent

課程名稱:"穿戴你的藝術 - Wear your art"

wk 2 blue = present, black = absent

1 陳薇曲 71010625

2 許瀅真 71010642

3 蔡佳宏 71010624

4 詹采漪 7990608 , gd focus.

5 陳亭君 7990622 gd

6 林豔君 71010650

7 吳孟勳 71010635 v gd notes, ideas. airw4967@gmail.com

8 陳韋靜 (audit) gd

9 周庭伊 (audit) gd

10 林俐wen (audit)

1// show and tell your Mannequin and the work - maybe another week to make it super fine?

2// watch Diana Vreeland documentary

3// what is the setting for your doll piece -

if the doll piece was designed for yourself - what are your settings?

4// do 4 variations of your final project idea.

Four sheets of A4 size, with color, collage, 2D models of your idea : expressions of your dreams and wishes

Description, Material, Size, and "Dream" (pitch)

5// Culture and Trends, Details Magazine... and many other google: styles...

http://www.details.com/culture-trends

http://www.simondoonan.com/

stylish playful wear - self expression

=====================================================================

Interesting reading for creators:

http://lifestyle.malaysia.msn.com/fashion/tipsntrends/photoviewer.aspx?cp-documentid=253607995

www.instructables.com

How to Make Your Own Luck

"All

creators need to be able to live in the shade of the big questions long

enough for truly revolutionary ideas and insights to emerge."

“You are what you settle for,” Janis Joplin admonished in her final interview. “You are ONLY as much as you settle for.” In Maximize Your Potential: Grow Your Expertise, Take Bold Risks & Build an Incredible Career (public library), which comes on the heels of their indispensable guide to mastering the pace of productivity and honing your creative routine, editor Jocelyn Glei and her team at Behance's 99U

pull together another package of practical wisdom from 21 celebrated

creative entrepreneurs. Despite the somewhat self-helpy, SEO-skewing

title, this compendium of advice is anything but contrived. Rather, it's

a no-nonsense, experience-tested, life-approved cookbook for creative

intelligence, exploring everything from harnessing the power of habit to cultivating meaningful relationships that enrich your work to overcoming the fear of failure.

“You are what you settle for,” Janis Joplin admonished in her final interview. “You are ONLY as much as you settle for.” In Maximize Your Potential: Grow Your Expertise, Take Bold Risks & Build an Incredible Career (public library), which comes on the heels of their indispensable guide to mastering the pace of productivity and honing your creative routine, editor Jocelyn Glei and her team at Behance's 99U

pull together another package of practical wisdom from 21 celebrated

creative entrepreneurs. Despite the somewhat self-helpy, SEO-skewing

title, this compendium of advice is anything but contrived. Rather, it's

a no-nonsense, experience-tested, life-approved cookbook for creative

intelligence, exploring everything from harnessing the power of habit to cultivating meaningful relationships that enrich your work to overcoming the fear of failure.In the introduction, Glei affirms the idea that, in the age of make-your-own-success and build-your-own-education, the onus and thrill of finding fulfilling work falls squarely on us, not on the "system":

If the twentieth-century career was a ladder that we climbed from one predictable rung to the next, the twenty-first-century career is more like a broad rock face that we are all free-climbing. There’s no defined route, and we must use our own ingenuity, training, and strength to rise to the top. We must make our own luck.

Stressing the importance of staying open and alert in order to maximize your “luck quotient,” Glei cites Stanford's Tina Seelig, who writes about the importance of cultivating awareness and embracing the unfamiliar in her book What I Wish I Knew When I Was 20:

Lucky people take advantage of chance occurrences that come their way. Instead of going through life on cruise control, they pay attention to what’s happening around them and, therefore, are able to extract greater value from each situation… Lucky people are also open to novel opportunities and willing to try things outside of their usual experiences. They’re more inclined to pick up a book on an unfamiliar subject, to travel to less familiar destinations, and to interact with people who are different than themselves.

But “luck,” it turns out, is a grab-bag term composed of many interrelated elements, each dissected in a different chapter. In a section on reprogramming your daily habits, Scott H. Young echoes William James and recaps the science of rewiring your “habit loops”, reminding us how routines dictate our days:

We can't, however, simply will ourselves into better habits. Since willpower is a limited resource, whenever we've overexerted our self-discipline in one domain, a concept known as “ego depletion” kicks in and renders us mindless automata in another. Instead, Young suggests, the key to changing a habit is to invest heavily in the early stages of habit-formation so that the behavior becomes automated and we later default into it rather than exhausting our willpower wrestling with it. Young also cautions that it's a self-defeating strategy to try changing several habits at once. Rather, he advises, spend one month on each habit alone before moving on to the next – a method reminiscent of the cognitive strategy of "chunking" that allows our brains to commit more new information to memory.If you think hard about it, you’ll notice just how many “automatic” decisions you make each day. But these habits aren’t always as trivial as what you eat for breakfast. Your health, your productivity, and the growth of your career are all shaped by the things you do each day – most by habit, not by choice.

Even the choices you do make consciously are heavily influenced by automatic patterns. Researchers have found that our conscious mind is better understood as an explainer of our actions, not the cause of them. Instead of triggering the action itself, our consciousness tries to explain why we took the action after the fact, with varying degrees of success. This means that even the choices we do appear to make intentionally are at least somewhat influenced by unconscious patterns.Given this, what you do every day is best seen as an iceberg, with a small fraction of conscious decision sitting atop a much larger foundation of habits and behaviors.

As both a lover of notable diaries and the daily keeper of a very unnotable one, I was especially delighted to find an entire section dedicated to how a diary boosts your creativity – something Virginia Woolf famously championed, later echoed by Anaïs Nin's case for the diary as a vital sandbox for writing and Joan Didion's conviction that keeping a notebook gives you better access to yourself.

Though the chapter, penned by Steven Kramer and Teresa Amabile of the Harvard Business School, co-authors of The Progress Principle, along with 13-year IDEO veteran Ela Ben-Ur, frames the primary benefit of a diary as a purely pragmatic record of your workday productivity and progress – while most dedicated diarists would counter that the core benefits are spiritual and psychoemotional – it does offer some valuable insight into the psychology of how journaling elevates our experience of everyday life:

Citing their research into the journals of more than two hundred creative professionals, the authors point to a pattern that reveals the single most important motivator: palpable progress on meaningful work:This is one of the most important reasons to keep a diary: it can make you more aware of your own progress, thus becoming a wellspring of joy in your workday.

Even more importantly, however, they argue that a diary offers an invaluable feedback loop:On the days when these professionals saw themselves moving forward on something they cared about – even if the progress was a seemingly incremental “small win” – they were more likely to be happy and deeply engaged in their work. And, being happier and more deeply engaged, they were more likely to come up with new ideas and solve problems creatively.

This, they suggest, can yield profound insights into the inner workings of your own mind – especially if you look for specific clues and patterns, trying to identify the richest sources of meaning in your work and the types of projects that truly make your heart sing. Once you understand what motivates you most powerfully, you'll be able to prioritize this type of work in going forward. Just as important, however, is cultivating a gratitude practice and acknowledging your own accomplishments in the diary:Although the act of reflecting and writing, in itself, can be beneficial, you’ll multiply the power of your diary if you review it regularly – if you listen to what your life has been telling you. Periodically, maybe once a month, set aside time to get comfortable and read back through your entries. And, on New Year’s Day, make an annual ritual of reading through the previous year.

This is your life; savor it. Hold on to the threads across days that, when woven together, reveal the rich tapestry of what you are achieving and who you are becoming. The best part is that, seeing the story line appearing, you can actively create what it – and you – will become.

The lack of a straight story line, however, might also be a good thing. That's what Jonathan Fields, author of Uncertainty: Turning Fear and Doubt into Fuel for Brilliance and creator of the wonderful Good Life Project, explores in another chapter:

Echoing John Keats's assertion that “negative capability” is essential to the creative process Rilke's counsel to live the questions, Richard Feynman's assertion that the role of great scientists is to remain uncertain, and Anaïs Nin's insistence that inviting the unknown helps us live more richly, Fields reminds us of what Orson Welles so memorably termed “the gift of ignorance”:Every creative endeavor, from writing a book to designing a brand to launching a company, follows what’s known as an Uncertainty Curve. The beginning of a project is defined by maximum freedom, very little constraint, and high levels of uncertainty. Everything is possible; options, paths, ideas, variations, and directions are all on the table. At the same time, nobody knows exactly what the final output or outcome will be. And, at times, even whether it will be. Which is exactly the way it should be.

Fields argues that if we move along the Uncertainty Curve either too fast or too slowly, we risk either robbing the project of its creative potential and ending up in mediocrity. Instead, becoming mindful of the psychology of that process allows us to pace ourselves better and master that vital osmosis between freedom and constraint. He sums up both the promise and the peril of this delicate dance beautifully:Those who are doggedly attached to the idea they began with may well execute on that idea. And do it well and fast. But along the way, they often miss so many unanticipated possibilities, options, alternatives, and paths that would’ve taken them away from that linear focus on executing on the vision, and sent them back into a place of creative dissidence and uncertainty, but also very likely yielded something orders of magnitude better.

All creators need to be able to live in the shade of the big questions long enough for truly revolutionary ideas and insights to emerge. They need to stay and act in that place relentlessly through the first, most obvious wave of ideas.

Nothing truly innovative, nothing that has advanced art, business, design, or humanity , was ever created in the face of genuine certainty or perfect information. Because the only way to be certain before you begin is if the thing you seek to do has already been done.

In another section, Stanford psychology Ph.D. candidate Michael Schwalbe turns to the intricate dance of risk-taking and the fear of failure. Citing the work of psychologists Daniel Gilbert, whose exploration of the art-science of happiness remains indispensable, and Timothy Wilson, whose work has revolutionized the way we think about psychological change, Schwalbe reminds us of the "impact bias" – our tendency to greatly overestimate the intensity and extent of our emotional reactions, which causes us to expect failures to be more painful than they actually are and thus to fear them more than we should. Schwalbe explains:

And yet Schwalbe reminds us that social science has invariably recorded that what people regret the most as they look back on their lives isn't what they attempted and failed at, but what they never tried in the first place:Gilbert and Wilson highlight two phenomena to explain this bias. The first is immune neglect. Just as we have a physical immune system to fight threats to our body, we have a psychological immune system to fight threats to our mental health. We identify silver linings, rationalize our actions, and find meaning in our setbacks. We don’t realize how effective this immune system is, however, because it operates largely beneath our conscious awareness. When we think about taking a risk, we rarely consider how good we will be at reframing a disappointing outcome. In short, we underestimate our resilience.

The second reason is focalism. When we contemplate failure from afar, according to Gilbert and Wilson, we tend to overemphasize the focal event (i.e., failure) and overlook all the other episodic details of daily life that help us move on and feel better. The threat of failure is so vivid that it consumes our attention. This happens in part because the areas of the brain we use to perceive the present are the same ones we employ to imagine the future. When we feel afraid of failing at a new business or anxious about the shame of letting investors down and what our peers will think, it’s hard to also imagine the pleasure we will get from our next venture and the other everyday activities that are a necessary and enjoyable part of life.

The solution, as a wise woman poignantly put it, seems to be: “Work as hard as you can, imagine immensities, don’t compromise, and don’t waste time. Start now. Not 20 years from now, not two weeks from now. Now.”Of the many regrets people describe, regrets of inaction outnumber those of action by nearly two to one. … We are left with a paradox of inaction. On one hand we instinctively tend to stick with the default, or go with the herd. Researchers call it the status quo bias. We feel safe in our comfort zones, where we can avoid the sting of regret. And yet, at the same time, we regret most those actions and risks we did not take.

Complement Maximize Your Potential with its equally insightful prequel, Manage Your Day-to-Day – but don't let yourself forget that the good life, the meaningful life, the truly fulfilling life, is the life of presence, not of productivity.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

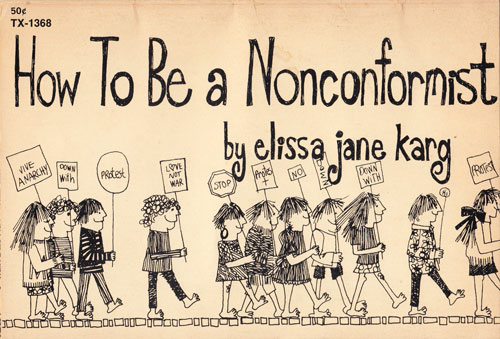

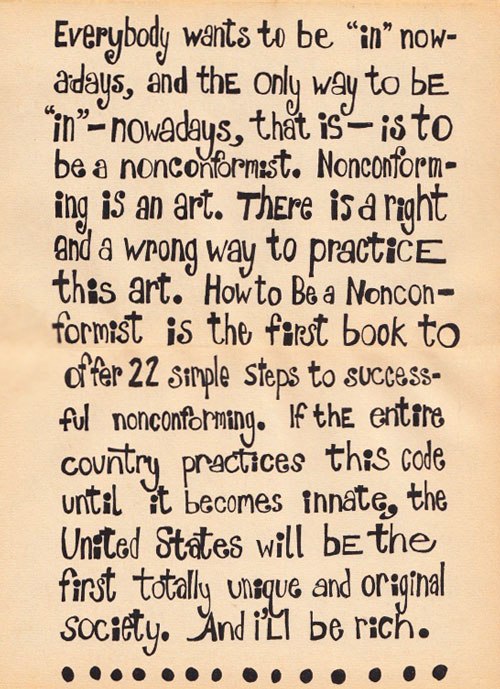

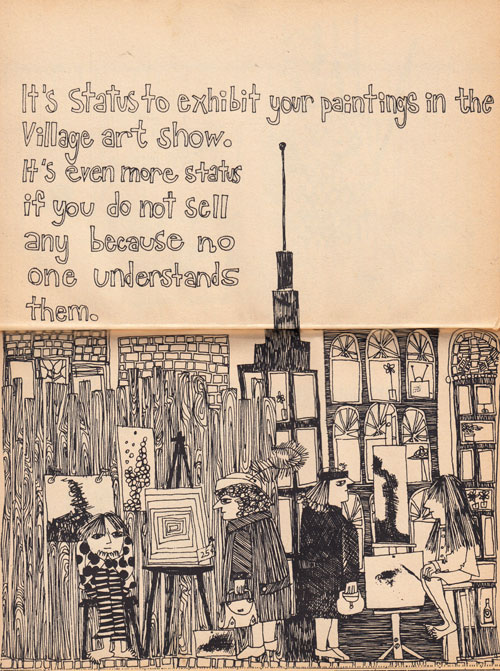

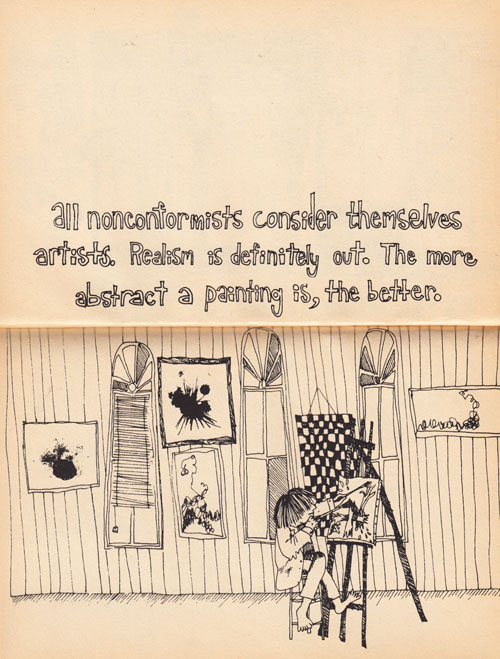

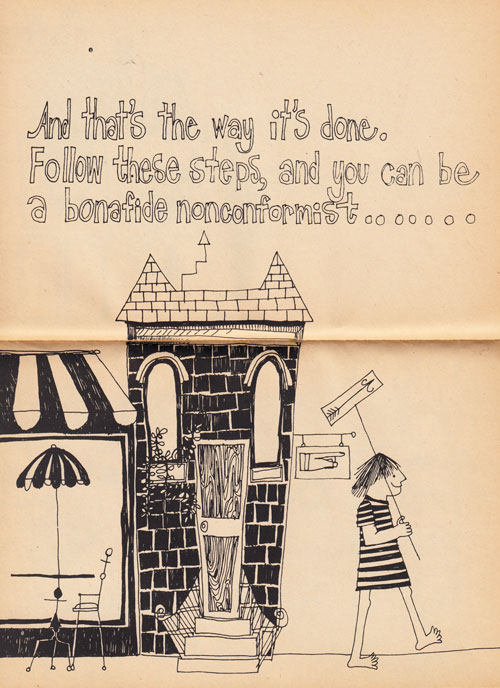

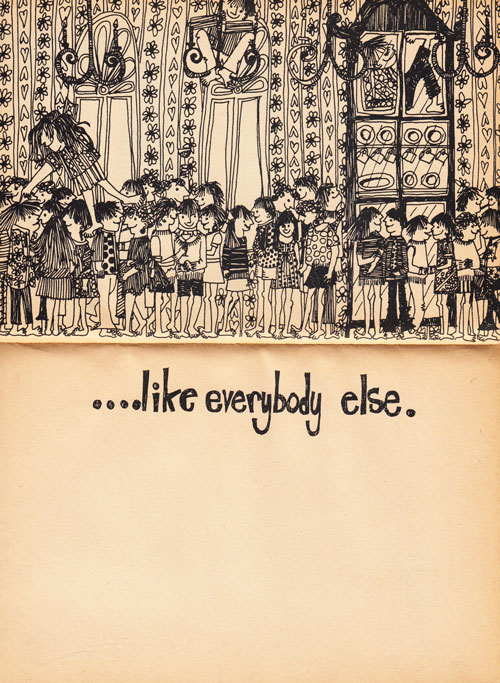

How To Be a Nonconformist: 22 Irreverent Illustrated Steps to Counterculture Cred from 1968

“Avoid socks. They are a fatal giveaway of a phony nonconformist.”

“Why do you have to be a nonconformist like everybody else?,” James Thurber asked in the caption to a 1958 New Yorker

cartoon depicting a woman fed up with her artist partner. It remains

unknown whether the cartoon itself, or this cultural dismay shared by

some of the era's counterculture thinkers, inspired the 1968 gem How To Be a Nonconformist (public library) by Elissa Jane Karg. One could easily imagine that if Edward Gorey, master of pen-and-ink irreverence, and Patti Smith,

godmother of punk-rock, had collaborated, this would've been the

result. But what's most impressive is that Karg was only sixteen at the

time, a self-described “cynical & skeptical junior at Brien McMahon

High School in Norwalk, Connecticut,” qualified to examine nonconformity

as “an angry and amused observer” of her “cool contemporaries.”

With her irresistibly wonderful black-and-white drawings and hand-lettered text, which originally appeared in her school newspaper and were eventually published by Scholastic, she offers 22 rules for becoming “a bona fide nonconformist,” poking fun at so many archetypes still strikingly prevalent – perhaps even amplified – today: the misunderstood artist-hipster, the troll grubbing for clout by spewing curmudgeonly comments, the protester-for-the-sake-of-

Karg, in true counter-nonconformist fashion, didn't end up moving to New York City and commodify her brand of creative cynicism. Instead, she moved to Detroit, had two daughters, joined the socialist party, became a nurse, and led an earnest life as an avid advocate for women's rights on the cusp of the second wave of feminism. Tragically, though perhaps poetically given her life choices, she was killed in 2008 at the age of 57 while riding her bicycle back from a socialist party meeting. She never authored another book, but did co-author the 1980 handbook Stopping Sexual Harassment.

Immeasurably wonderful, How To Be a Nonconformist is long out of print but surviving copies of can be found online. Complement it with Exactitudes, the modern-day photo-anthropological record of the cultural phenomenon Karg satirizes.

:: MORE IMAGES / SHARE ::

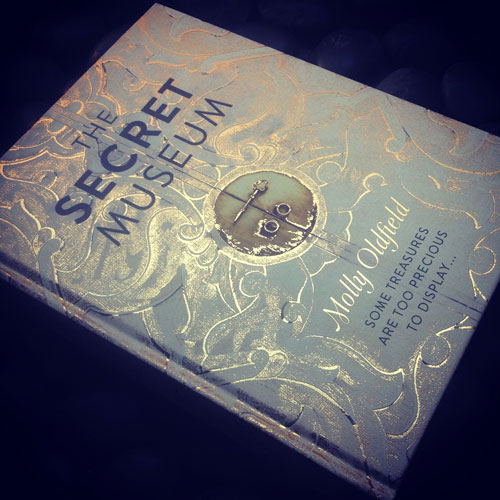

The Secret Museum: Van Gogh's Never-Before-Seen Sketchbooks

A bittersweet record of artistic genius and unlived dreams.

Given my soft spot for the sketchbooks of famous artists and private notebooks of great creators, I was delighted to discover that, unbeknownst to most, Vincent van Gogh

kept one. In an 1882 letter to his brother Theo, he wrote: “My

sketchbook shows that I try to catch things ‘in the act.’” This private

record of the artist's genius, however, has remained obscured from

public view. Thankfully, Molly Oldfield brings this hidden gem to light in The Secret Museum (public library) – the same magnificent tome that gave us the surprisingly dark story of how the Nobel Prize was born

– which culls sixty never-before-seen "treasures too precious to

display" from the archives and secret storage locations of some of the

world's top cultural institutions.

Given my soft spot for the sketchbooks of famous artists and private notebooks of great creators, I was delighted to discover that, unbeknownst to most, Vincent van Gogh

kept one. In an 1882 letter to his brother Theo, he wrote: “My

sketchbook shows that I try to catch things ‘in the act.’” This private

record of the artist's genius, however, has remained obscured from

public view. Thankfully, Molly Oldfield brings this hidden gem to light in The Secret Museum (public library) – the same magnificent tome that gave us the surprisingly dark story of how the Nobel Prize was born

– which culls sixty never-before-seen "treasures too precious to

display" from the archives and secret storage locations of some of the

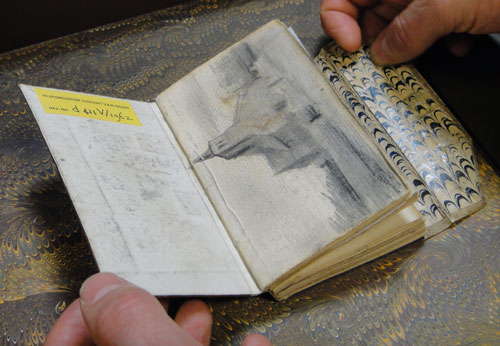

world's top cultural institutions.At Amsterdam's Van Gogh Museum, Oldfield finds the artist's seven surviving sketchbooks, only four with their original cover, meticulously stored in the prints and drawings archive. The early sketchbooks bespeak Van Gogh's religious upbringing and how he transformed that spiritual intensity into a creative practice. Oldfield writes:

Van Gogh had been all set for a deeply religious life but, aged 26, he transferred his religious zeal to art. He decided to become an artist instead, as he felt he wanted to leave “a certain souvenir” to humankind “in the form of drawings or paintings, not made to comply with this or that school but to express genuine human feeling.” He moved to a rural town called Nuenen to live with his parents and begin learning his craft.

The first sketchbook

Leafing through countless pages of his sketchbooks, Oldfield reflects

on this record of the artist's creative journey and the bittersweet

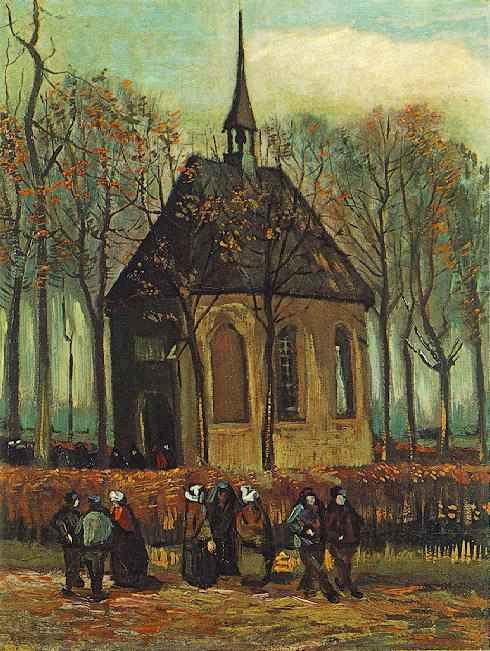

memento the sketchbook provides:The first sketchbook has a royal blue, marbled inside cover and an empty pocket at the back. The first image he sketched in it was a church in Nuenen. He later painted this church in View of the Sea at Scheveningen and Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church at Nuenen.

‘View of the Sea at Scheveningen’ by Vincent van Gogh, 1882

Curiously, the two paintings once hung in the Amsterdam museum but

were stolen in 2002. It remains unknown where they are or who took them,

and the pencil sketch from Van Gogh's notebook endures as the only

trace of the missing masterpieces.

‘Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church at Nuenen’ by Vincent van Gogh, 1884

The remaining pages of the first notebook are filled with drawings of

people and places, capturing rural life in Nuenen. The second

sketchbook, with a black cover, continues with glimpses of Nuenen, then

turns to Antwerp, where Van Gogh moved in November of 1885. It was there

he developed his passion for Japanese woodblock prints. Soon, however,

the artist – who had been sustaining himself primarily on bread, coffee

and absinthe – fell ill and moved to Paris to live with his brother,

beginning his third sketchbook – a rectangular giant compared to his

previous pocket-sized books lined in linen – which he filled with

drawings of Parisian people and museum sculptures, as well as the female

nudes who posed for him. Oldfield marvels:Still enchanted by the countryside, however, Van Gogh left Paris in 1888 and settled in Arles in the south of France. There, she met a thirteen-year-old girl named Jeanne Calment, who sold the artist colored pencils at her uncle's shop. She described Van Gogh as “dirty, badly dressed, and disagreeable.” (Curiously, Jeanne outlived the artist by more than a century and died in 1997 at the age of 122.) Disagreeable as he might have been, however, Van Gogh felt lonely and aspired to create an artist colony in Arles. Eventually, Paul Gauguin joined him and the two artists lived together in the famed Yellow House, with a painting of sunflowers gracing Gauguin's room.In one pencil sketch, I recognized the windmill at Montmartre – a rural village at the time – which appears in lots of his paintings. Also in this book are sketches of flowers, Theo van Gogh's laundry list and a letter from Vincent to Theo written in chalk. There is only one stray sheet, which the artist tore out in order to write a note to his brother announcing his arrival in the city.

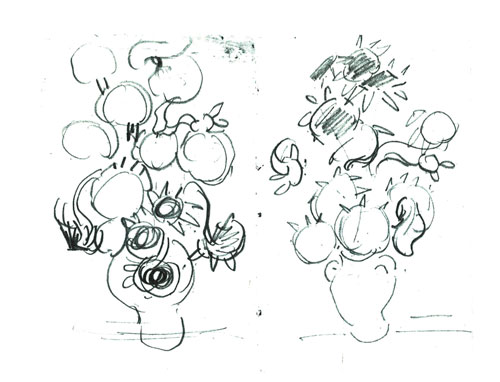

Van Gogh's sunflower sketches from the final sketchbook

It was only in the final sketchbook – an elegant one with a linen

jacket and a tie to keep it closed – that Van Gogh sketched the first

versions of his iconic series Sunflowers. Oldfield laments:Van Gogh's artistic dream, however, soon became a nightmare. Residents of Arles petitioned that he be evicted from the Yellow House on account of his madness and he soon moved into an asylum, where he continued to paint. In May of 1890, he left the clinic and move to the Auvers-sur-Oise commune in northwestern France to be close to his physician and his brother. Two months later, he shot himself, believing he was a failure and leaving behind his final sketchbook as the forlorn ghost of his unlived dream. Oldfield ponders:Having never sold a painting in his life, at that moment, Van Gogh would never have conceived of a time when his sunflowers would be instantly recognized across the planet.

There are two sketches of sunflowers in the final book. One shows 16 sunflowers in a vase; the other 12 stems in a vase. The drawings match up with two paintings that belong to the Van Gogh Museum; they have the same number of flowers in the vases. Perhaps he was sketching and remembering happier times. … I wonder, if he had known what would become of his paintings, would he have shot himself? And, if he had not, what other paintings might he have produced?

The Secret Museum absolutely fascinating in its entirety, featuring such rare cultural treasures as a piece of Newton's apple tree painstakingly preserved at London's Royal Society, an original Gutenberg Bible printed on vellum at New York's Morgan Library, and Nabokov's cabinet of butterfly genitalia held at Harvard.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

Alone in the Forest: Exploring Fear & Courage in Stunning Illustrations Based on Indian Folk Art

Exquisite

visual storytelling that speaks both to our crippling fear of the

unfamiliar and our ability to transcend it, emerging enriched by the

experience.

For nearly two decades, Indian independent publisher Tara Books

has been giving voice to marginalized art and literature through a

commune of artists, writers, and designers collaborating on beautiful

books based on Indian folk art traditions, including some extraordinary handmade gems that made it into my recent collaboration with the New York Public Library. Now comes Alone in the Forest (public library),

illustrated by the celebrated Gond tribal artist Bhajju Shyam. It tells

the tale of Musa, a young Indian boy, and his frightening foray into

the dark forest to fetch firewood after his mother falls sick. Somewhere

between Lemony Snicket's The Dark and Tara's magnificent The Night Life of Trees – in which Shyam's expressive illustrations also appear – this exquisite piece of storytelling speaks both to our crippling fear of the unfamiliar and our ability to transcend it and emerge somehow enriched by that experience.

For nearly two decades, Indian independent publisher Tara Books

has been giving voice to marginalized art and literature through a

commune of artists, writers, and designers collaborating on beautiful

books based on Indian folk art traditions, including some extraordinary handmade gems that made it into my recent collaboration with the New York Public Library. Now comes Alone in the Forest (public library),

illustrated by the celebrated Gond tribal artist Bhajju Shyam. It tells

the tale of Musa, a young Indian boy, and his frightening foray into

the dark forest to fetch firewood after his mother falls sick. Somewhere

between Lemony Snicket's The Dark and Tara's magnificent The Night Life of Trees – in which Shyam's expressive illustrations also appear – this exquisite piece of storytelling speaks both to our crippling fear of the unfamiliar and our ability to transcend it and emerge somehow enriched by that experience.

The Gonds of central India, among whom Shyam came of age, are a community of exceptionally visual people with a heritage of forest-dwellers. Though their art tradition originates from the decorative patterns painted on the mud floors and walls of their homes – a medium widely used across rural India and also employed by the Warli and Meena tribes – it has blossomed over the centuries into a visual language of extraordinary richness and storytelling capacity.

Complement Alone in the Forest with more of Tara's treasures, including their two crown jewels, The Night Life of Trees and Waterlife, their homage to cats, and my personal favorite, the ever-empowering Drawing from the City.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。